Over the past two years, generative AI has rapidly penetrated the legal industry, prompting law firms to develop clear policies on how attorneys may use AI tools internally and what to disclose to clients about AI-assisted work. This report provides a comprehensive overview of U.S. law firms’ approaches to AI usage, including internal policy frameworks for employees, client-facing disclosure practices, industry adoption trends, and criteria firms use to vet and integrate AI platforms. Real examples of policy language and emerging best practices from bar associations are included to illustrate the current standards.

Industry Trends: From Early Caution to Increasing Adoption

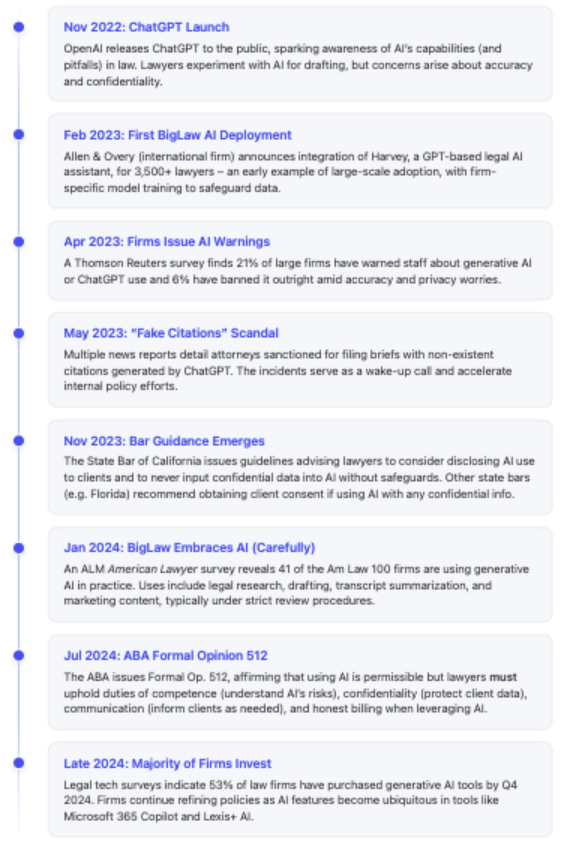

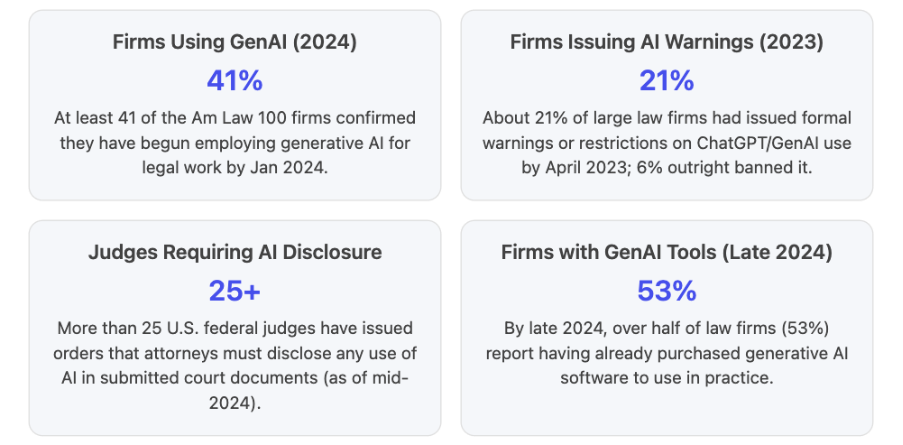

Generative AI’s debut in late 2022 (with tools like ChatGPT) sparked both excitement and anxiety in law firms. In early 2023, many firms took a cautious stance: a Thomson Reuters survey found that 15% of firms (and 21% of large firms) had issued formal warnings about using generative AI or ChatGPT at work, and 6% outright banned unauthorized use 1. Top concerns included accuracy (“AI hallucinations”) and data privacy – lawyers worried AI might fabricate case law or inadvertently leak sensitive information 2 3. A series of highly publicized incidents underscored these risks, such as court sanctions against attorneys who submitted AI-generated briefs with fake citations in mid-2023 4 5.

However, as the year progressed, competitive and client pressures began to push firms toward controlled experimentation with AI. By late 2023, many law firms recognized the potential efficiency gains of tools that could speed up legal research, drafting, and document review. In fact, 77% of firms cited increased efficiency as a primary benefit of AI in practice 6. Large firms in particular started carefully piloting generative AI in non-sensitive contexts. Most firms avoided feeding client data into open public models, but a handful began testing AI on closed, secure systems (often with client permission for specific projects). For example, some firms partnered with legal-specific AI providers to try tools on internal data in a sandbox environment, ensuring no confidentiality breach.

By early 2024, adoption had accelerated notably. The American Lawyer surveyed the top 100 U.S. firms (the “Am Law 100”) and found at least 41 firms had begun employing generative AI in some form 7. Lawyers at these firms were using AI assistants to research legal issues, generate first-draft memos and briefs, summarize transcripts, and assist with marketing content creation 8. On the business side, marketing and knowledge management staff were saving hours by using AI for drafting newsletters, social media posts, and mining internal data 9. Importantly, even those adopting AI tended to do so under tight controls, often limiting use to specific use-cases or requiring case-by-case approvals. For instance, most firms still prohibited inputting any client-identifying facts into tools like ChatGPT unless it was a specially approved platform with safeguards 10 11.

Meanwhile, industry guidelines and client expectations quickly evolved. Corporate clients began inquiring in RFPs and meetings how their law firms were leveraging AI to be more efficient 12. In response, some forward-looking firms started highlighting “responsible AI usage” as a value-add. At the same time, clients (especially in regulated industries) wanted reassurance that their lawyers wouldn’t expose sensitive data to AI. Some company legal departments even instructed outside counsel “do NOT use generative AI on our work without our consent”, reflecting confidentiality concerns 13.

Regulators also stepped in. By mid-2024, over 25 federal judges had issued standing orders requiring attorneys to disclose AI use in court filings 14. Bar associations formed committees and published guidance (discussed further below) urging attorneys to maintain competence and care when using AI and to consider informing clients about its use 15 16. The American Bar Association in July 2024 released Formal Opinion 512, its first ethics opinion on generative AI, underscoring that existing ethical duties (competence, confidentiality, communication, and reasonable fees) fully apply to AI 17 18.

By 2025, the landscape has shifted to “cautious adoption.” Surveys indicate more than half of law firms have now invested in generative AI software or platforms for legal work 19. Many routine legal tech products (from Westlaw and Lexis to Microsoft Office) now bake in AI features, making it hard for lawyers to avoid generative AI entirely 20. The consensus in BigLaw is that completely shunning AI is impractical – instead, the focus is on using it responsibly under rigorous policies. Below, we detail what those internal AI use policies typically entail and how firms are communicating AI use to clients.

Internal AI Use Policies: How Law Firms Govern Employee Use of AI

Virtually all U.S. law firms that permit AI use have instituted internal policies or guidelines to regulate how attorneys and staff may use AI tools on the job. These policies aim to harness AI’s benefits (efficiency, insights) while mitigating risks (confidentiality breaches, ethical lapses, inaccurate outputs). Although each firm’s policy is unique, common themes and rules have emerged across the industry:

- Confidentiality and Data Security: Protecting client information is the cornerstone of every firm’s AI policy. Lawyers are strictly prohibited from inputting any confidential or sensitive client data into AI tools unless those tools have been vetted and approved for such use with appropriate safeguards 21 22. For example, a sample BigLaw policy states: “Confidential client information … may never be uploaded or input into \[generative AI] technology. Once information becomes part of a GenAI program’s dataset, the Firm can no longer control that information” 23. In practice, this means attorneys cannot paste client documents or specifics into ChatGPT or public AI services. Instead, firms permit using AI on general tasks or with anonymized data. If a use-case does involve client data (say, analyzing a contract draft), only firm-approved platforms that ensure no data is shared or retained externally may be used 24. Many firms maintain a whitelist of “approved AI tools” which meet their security and privacy standards (for instance, an AI tool that promises no training on user-provided inputs and robust encryption) 25. Some firms even deploy self-hosted or private-instance AI solutions to keep all data in-house. The driving principle is to avoid any breach of attorney–client privilege or confidentiality through AI 26 27.

- Accuracy, Verification and “Human in the Loop”: Another universal rule is that AI-generated output must be treated as a draft – never final. Lawyers remain responsible for the accuracy and quality of any work product. Thus, internal guidelines mandate that attorneys must carefully review and verify AI outputs before using them in any legal document or communication 28 29. Many policies explicitly require cite-checking and fact-checking of AI-generated text. For example, one firm’s guideline instructs: “Under no circumstances shall work product generated in whole or in part by GenAI be filed with a court or circulated outside the Firm unless and until all facts and legal citations are checked and verified by a human.” 30. This addresses the “hallucination” problem – AI tools have been known to produce plausible-sounding but false information if not overseen 31 32. By enforcing human verification, firms seek to prevent mishaps like fictitious case citations or misstatements of law. In short, AI may assist with a first draft or research, but it does not get the last word – a lawyer must validate everything. Some firms also impose record-keeping requirements: if an attorney uses an AI tool in producing work, they may be asked to save the query and response (e.g. download the chat transcript to an internal system) for transparency and potential audit 33.

- Legal Professional Oversight and Limitations: Firms emphasize that AI is a tool to augment, not replace, human lawyers. Internal policies remind attorneys that using AI does not absolve them of professional duties or judgment 34 35. For instance, one sample policy states: “AI may be used to assist, but not replace, legal reasoning or decision-making. Attorneys remain solely responsible for all legal advice and work product.” 36. Accordingly, certain uses of AI are typically off-limits. Common prohibited uses include: letting AI draft legal advice or court filings without attorney review, relying on AI to predict case outcomes or set legal strategy without human analysis, or using AI in ways that would violate laws or ethics (for example, to circumvent laws against discrimination in decision-making) 37. Some firms expressly ban using generative AI for sensitive legal tasks like making judgment calls on case strategy, client counseling, or any final legal conclusions – those must come from a human attorney. The tone of these provisions makes clear that the lawyer is the decision-maker, and AI is just an assistant. Many policies also warn against over-reliance on AI: attorneys shouldn’t become complacent or trust an AI output without scrutiny, since that could undermine the duty of competence and diligence owed to clients 38 39.

- Ethical Compliance (Competence, Bias, Supervision): To comply with evolving ethics guidance, internal policies often incorporate specific reminders of attorneys’ ethical obligations when using AI. The ABA and state bars have highlighted Model Rules that are implicated – e.g. Rule 1.1 (Competence) requires lawyers to understand “the benefits and risks” of relevant technology 40. In line with this, firms are instructing their lawyers to educate themselves on AI’s limitations. One firm guideline reads: “Consistent with an attorney’s duty of competence, \[Firm] encourages attorneys and staff to educate themselves on GenAI and how it is used in their practice. Technological proficiency is required at this Firm.” 41. Training sessions on safe AI use are becoming common, and some firms mandate completion of AI-specific CLE or internal training before lawyers can access certain AI tools 42. Avoiding bias is another concern – lawyers are cautioned to be alert to potential biases in AI outputs (which might reflect biases in training data) and to ensure AI use doesn’t lead to unethical or discriminatory outcomes 43 44. Supervision duties also extend to AI: partners must ensure that if junior lawyers or staff use AI in work for a client, it’s consistent with firm policy and properly overseen 45. In essence, firms are transplanting traditional legal ethics principles into their AI policies: maintain competence (know what you’re doing with the tool), uphold confidentiality, be honest (no falsehoods from AI), ensure communication (which includes telling clients about AI when appropriate, as discussed later), and supervise the work just as if a junior lawyer had drafted it 46 47. The ABA Formal Opinion 512 (2024) reinforces these points, and firms are aligning internal rules accordingly 48 49.

- Internal Transparency and Approvals: Many firms require a degree of internal transparency about AI use, to maintain quality control. Lawyers and support staff are often instructed to notify their supervising attorney or practice group leader if they plan to use AI in a matter 50. This allows the firm’s management to ensure usage is appropriate and policy-compliant. For example, a policy might require that an attorney “must affirmatively advise all supervising attorneys when GenAI will be or has been used in the creation of work product” 51. Some firms set up an internal review or approval process: e.g., attorneys must get clearance from an IT security team or an AI committee before using a new AI tool or before using AI on particularly sensitive cases. This mirrors how firms handle other novel technology – through oversight. Additionally, firms may impose use limits, such as restricting AI usage to non-billable exploratory tasks unless approved. All these measures ensure that partners and risk managers have visibility into when and how AI is being utilized internally.

- Ongoing Monitoring and Iteration: Recognizing that AI technology and regulations are quickly evolving, firms often include provisions that policies will be revisited and updated regularly 52. Some have formed dedicated AI task forces or working groups that meet to evaluate new AI tools and update best practices. For instance, a firm might state that its AI policy is subject to change as laws change, and that attorneys will be notified of updates and may need to attend additional training 53. This flexibility is important – what is unacceptably risky today (e.g. using a public AI for a confidential task) might become safer tomorrow if new solutions or legal standards emerge, and vice versa. Firms are essentially in a phase of constant learning with AI, and internal policies are treated as living documents, much like cybersecurity policies.

In summary, internal AI use policies in law firms enforce a “crawl before you walk” approach: lawyers may experiment with AI’s productivity benefits, but only within strict guardrails that protect client interests. Confidentiality must not be compromised, every AI output must be vetted by a lawyer, and all usage must conform to ethical and professional standards 54 55. By setting these rules, firms aim to capture AI’s upside (faster drafting, better data analysis, etc.) without falling foul of their legal duties. As one bar association comment put it, *a well-crafted AI policy ensures “responsible innovation” – embracing tech advancements while maintaining the profession’s high standards of accuracy, integrity, and client service 56 57.*

Client-Facing Policies: Disclosure of AI Usage and Managing Client Expectations

Beyond internal controls, law firms also grapple with what – if anything – to tell clients about the use of AI in delivering legal services. This area is rapidly evolving. Traditionally, lawyers haven’t detailed to clients every tool or research method they use. However, generative AI raises new questions: Do clients have a right to know if an AI helped draft their contract? Should lawyers obtain consent before using AI on a client’s matter, especially if it might expose client data? Firms are approaching these questions with care, balancing transparency with practicality. Key patterns in client-facing AI policies and disclosures include:

- Proactive Disclosure vs. Case-by-Case: A growing consensus is that transparency with clients about AI use is a best practice, at least in this “transitional” phase of generative AI. In fact, some courts now effectively require transparency (with judges mandating attorneys disclose AI usage in filings) 58. Many law firms have begun addressing AI in their engagement letters or client service agreements. For example, firms may include a clause explaining that they reserve the right to use reputable AI tools to assist in the work – under attorney supervision – to increase efficiency 59. Below is an illustrative engagement letter clause adapted from guidance by the State Bar of Texas:

Use of Artificial Intelligence: “The Firm may use reputable artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to support legal research, document review, drafting, and other tasks in the course of the representation. Any such tools are used under attorney supervision and do not substitute for the professional judgment of our lawyers. The Firm will not input identifiable client information into AI tools that store or use data for future training, unless deployed in a private, secure environment. All AI use will comply with our duties of confidentiality and applicable law.” 60 61

This kind of disclosure puts the client on notice that AI might be involved behind the scenes, but also assures them that human lawyers remain fully in control and confidentiality is protected. In practice, firms taking this approach often find clients appreciate the transparency. It preempts questions and demonstrates the firm is being thoughtful. Some clients are indifferent as long as quality is high; others with stricter data policies may ask for more information or opt-out.

Not all firms have a blanket disclosure yet – some handle it case-by-case. For instance, a firm might not mention AI in standard engagement terms, but instruct its lawyers: “be transparent with clients about the use of GenAI when appropriate and if asked”

62. In other words, if a client inquires or if AI played a significant role in a deliverable, the lawyer should candidly discuss it. A managing partner at one firm noted he “couldn’t imagine using \[AI] on a client matter on a not fully-disclosed basis” if it materially affected the work 63. Several large law firms have reported that certain clients explicitly direct them not to use generative AI without prior communication 64. In those cases, firms will abide by the client’s instructions – e.g., pausing any AI use or obtaining detailed consent for specific tasks. On the other hand, some tech-savvy clients encourage their firms to leverage AI for efficiency, as long as proper safeguards are in place 65.

The trend is clearly toward more upfront communication. The State Bar of California’s Generative AI guidance (Nov 2023) advised lawyers to consider disclosing the use of AI to clients, including discussing the technology’s novelty and risks 66 67. The Florida Bar’s draft opinion (2023) went further to say attorneys should obtain informed client consent before using genAI if any confidential information would be involved 68. And the ABA Formal Op. 512 (2024) stops short of requiring across-the-board disclosure, but under Model Rule 1.4 on communication, if AI usage is part of “the means by which the client’s objectives are accomplished,” a lawyer should reasonably consult with the client about it 69. In plain terms, if using AI could significantly impact the representation (affect costs, confidentiality, or outcomes), the client should be in the loop 70.

- Scope of Disclosure – What to Tell the Client: When firms do communicate about AI, they typically cover a few key points to reassure the client:

- Nature of AI Use: They explain what tasks AI is used for (e.g. “to assist with research, drafting or analysis”) and emphasize that it’s an efficiency tool under lawyer supervision, not an independent decision-maker 71 72. Clients are thereby assured that a competent attorney is checking all work.

- No Compromise to Confidentiality: Firms explicitly affirm that client-identifying or sensitive details will not be exposed to any AI platform that doesn’t guarantee privacy 73. They might mention using AI in a “secure environment” or not at all if the AI is a public model. This directly addresses clients’ biggest fear – that their data might leak into some AI training set. For example, a disclosure might say “The Firm will not disclose identifiable client information or input it into any AI system that might store or learn from it, absent client permission” 74.

- Compliance and Quality Measures: Some firms note that all use of AI will adhere to ethical rules and quality controls 75. They may explain that attorneys validate AI outputs, so the client understands that using AI won’t diminish the quality or accuracy of the work product. If AI is expected to reduce the time spent (and thus fees), firms might highlight that benefit too.

- Client’s Right to Discuss or Decline: Best practices suggest inviting the client’s input. A disclosure clause may add that the firm is happy to answer any questions about AI use and can adjust its approach if the client has concerns 76 77. This opens the door for clients to say, “Actually, we prefer you don’t use AI on this matter,” or conversely, “Feel free to use it as much as possible if it saves time.”

The form and detail of disclosure can depend on the client’s sophistication. A tech industry client might be quite comfortable after a brief mention, whereas a financial institution might require a more in-depth conversation about how, for example, an AI contract review tool works and what data it touches. Lawyers are tailoring the discussion to the client. The MIT Task Force on AI and the Law (2023) suggested that engagement terms should specifically address AI use and that with some clients, formal consent (not just disclosure) may be appropriate

78 79.

- How Disclosure Impacts Client Consent and Billing: One practical aspect is billing and client consent for AI-derived efficiencies. If AI helps produce work faster, do clients get a cost savings? Most firms have not promised automatic discounts, but the ABA ethics guidance on fees says a lawyer must charge reasonable fees even when using AI – you can’t bill hours you didn’t work or bill for “learning to use the AI” 80. Typically, the time an attorney spends prompting an AI and then reviewing its output is billable (since that is genuine work), but the time the AI “spent” drafting instantly is not billable. Several firms have updated internal billing policies accordingly (e.g., a lawyer can bill the 0.2 hours spent reviewing an AI-generated research memo, but not add an extra hour as if they wrote it from scratch). When discussing AI with clients, lawyers may mention that AI use can reduce the overall time required for certain tasks, which could make the representation more cost-effective for the client 81. Some engagement letters address this by noting any impact on fees or explicitly stating that the client will not be charged for work not performed by a human 82.

- Client Reactions and Firm Practices: So far, client reactions to AI disclosures have varied. According to a Bloomberg Law report, some clients have proactively asked their firms whether and how they use AI 83. In certain sectors, clients have even added questions about AI policies in outside counsel guidelines, effectively setting their expectations (for example, requiring notification before AI is used on their matters) 84. A partner at Paul Weiss (a large NY firm) noted that their standard engagement letter did not yet routinely include AI language, but they have clients who insist on “no AI without telling us,” and of course, “ultimately, you follow your client’s instructions.” 85. Many firms are in a similar interim state: they have the capacity to use AI and policies governing it, but they will defer to a given client’s comfort level on a case-by-case basis.

On the flip side, clients are also increasingly expecting firms to leverage technology efficiently. General Counsels have indicated they don’t want to pay for avoidable manual drudgery if AI could handle it more cheaply (with the lawyer’s oversight). As one GC put it, if outside lawyers can use AI to be faster and cheaper and still accurate, that’s generally welcome – but the client wants to be confident that it’s done carefully

86 87. This dynamic is driving firms toward transparent but positive messaging: essentially, “Yes, we intelligently use new tools to be efficient, but we do so safely and you’ll always get high-quality, attorney-verified work product.” In other words, disclosure is framed as an assurance, not a warning.

- Future Outlook for Client Disclosures: As AI becomes a routine part of legal workflows (often invisibly embedded in software), some predict that granular disclosures will eventually wane. If every tool (from Microsoft Word to document management systems) has AI features, it may not be practical to notify clients of each instance 88. Instead, broad up-front transparency might suffice. For now, though, we are in a period where AI is novel enough that many firms err on the side of telling clients about it, especially for significant uses. We’re also seeing industry standards coalesce: if AI was materially involved in a deliverable, it’s prudent to mention it to the client, either in the cover email or in a brief note in the document. And if a client has expressed any reservations, firms will either avoid AI or seek explicit permission. This approach aligns with the duty to communicate and with building trust – surprises regarding AI usage are what firms want to avoid.

In summary, client-facing AI policies emphasize clarity and consent. Firms are striving to educate clients that AI is simply another tool (like an advanced software) the firm might use to serve the client efficiently, and that all ethical and quality safeguards remain in place 89. By integrating AI disclosures into engagement letters or project discussions, law firms foster an environment where clients are informed partners in how cutting-edge technology is applied to their legal matters. This transparency will be crucial for broader acceptance of AI in legal services.

Choosing and Vetting AI Platforms: How Firms Decide What Tools to Use

Not all AI tools are created equal, and law firms are extremely selective about which AI platforms or software they allow into their workflows. The decision to implement an AI tool – whether it’s a commercial product or a custom system – involves rigorous vetting against security, ethical, and performance criteria. Here’s how firms typically decide what AI platforms can be implemented or integrated into their environment (sometimes described as integrating into the firm’s “data pool” or knowledge systems):

- Data Privacy and Security First: The foremost criterion is protecting confidential data. Firms will only adopt AI solutions that demonstrate robust data privacy safeguards. This means:

- No Unauthorized Data Sharing: The AI tool must not send the firm’s or clients’ data to any external party or use it to train public models 90 91. Many vendors now offer “enterprise” AI models that guarantee user data is isolated and not used to improve the model for others. For example, OpenAI offers a business version where chat data isn’t used for training. Law firms insist on such guarantees in contracts 92.

- Encryption and Access Control: The platform should use strong encryption for data in transit and at rest, and allow the firm to control who can access the AI and its outputs. Integration with the firm’s single sign-on or other access management is a plus. Essentially, the AI system should fit into the firm’s IT security architecture like any other approved software.

- On-Premises or Private Cloud Options: Many firms prefer AI models that can be deployed behind the firm’s firewall or in a private cloud instance. By having a dedicated instance, the firm ensures that its data and prompts do not co-mingle with others’. For example, when Allen & Overy deployed Harvey AI, the model was fine-tuned on A&O’s own data and “firewalled” so that A&O’s usage would remain separate and confidential 93. Keeping the AI as an internal tool gives the firm full control. If a tool can only be accessed as a public SaaS with unknown handling of data, most firms will reject it.

- Vendor Reputation and Compliance: Firms perform due diligence on the AI vendor’s privacy policies and compliance record. They check if the provider will sign a strong confidentiality agreement. They also consider jurisdictional issues (where is the data stored? does it comply with GDPR, CCPA, etc., in case of cross-border data). If a vendor cannot answer these questions satisfactorily, the tool won’t be adopted. In short, a law firm’s AI platform must meet the same standards as a bank’s or hospital’s would, given the sensitivity of legal data.

- The AI Model and Legal Domain Fit: Law firms scrutinize the technical nature of the AI model to ensure it is suitable for legal work:

- Model Type and Training Data: Firms examine what underlying AI model powers the tool (e.g., GPT-4, a custom large language model, etc.) and, crucially, what data it was trained on 94. They strongly prefer models that have been trained or fine-tuned on legal data – such as case law, statutes, contracts, etc. – rather than just general internet text 95. A model with legal training is more likely to produce relevant and accurate outputs for lawyers. For instance, LexisNexis’s new GenAI tools are built on legal datasets, which firms find appealing 96. If a model can’t understand legal terminology or reasoning, it’s not much use.

- Ability to Fine-Tune or Customize: An ideal platform allows the firm to further fine-tune the AI on the firm’s own knowledge base (briefs, memos, templates). This can make the AI more accurate in the firm’s specialties and also ensures the firm’s data stays in its own instance 97 98. Many large firms are exploring solutions where they effectively get a “private LLM” that they can train continuously on their internal data. This both improves relevance and keeps data internal. If an AI tool does not offer any customization or training on proprietary data, the firm will consider whether its out-of-the-box performance is still acceptable.

- Transparency and Explainability: Firms favor AI tools that provide some transparency in how they work. This could mean the tool gives source citations for its outputs, or it can show which references it relied on. Legal AI products that can cite to underlying cases or documents are heavily favored, because lawyers need to verify every statement 99. For example, an AI brief writer that provides footnote citations is more trusted than one that produces uncited text. If the tool uses multiple AI models or a hybrid approach (like retrieving relevant documents then summarizing), firms want to know that. They also assess whether the vendor is forthcoming about the model’s limitations and behavior.

- Model Performance (Accuracy & Limitations): Law firms often conduct internal tests or pilots to evaluate accuracy. If a tool is advertised to answer legal questions, the firm might have a group of attorneys throw a set of questions at it and then evaluate the correctness of answers. They will measure the “hallucination rate” – how often it makes things up. As one study noted, even legal-specific models can still generate some incorrect info (e.g. Lexis+ AI reportedly gave wrong info ~17% of the time in tests) 100. Firms need the error rate to be acceptably low and manageable with human oversight. If a tool hallucinated frequently or made egregious errors in pilot, it likely won’t be approved for real use. Quality assurance is key: the tool doesn’t have to be perfect (humans aren’t either), but it must be reliable enough that with reasonable vetting an attorney can confidently use its output.

- Use Case Specific Models: Sometimes a combination of models is best. Firms may use a simpler or smaller model for one task and a larger one for another, or a tool that ensembles models. For instance, an AI tool might use a factual database lookup model plus a generative model, which can increase accuracy. Law firm tech teams consider these architectures as well – whether the model is optimized for the tasks the firm cares about (contract analysis vs. brief writing vs. e-discovery summaries, etc.) 101 102.

- Functionality and Integration: A practical factor is how well the AI tool integrates with the firm’s existing systems and workflows:

- Document Management Integration: Lawyers work out of document management systems (DMS) like iManage or cloud drives. An AI tool that can plug into the DMS to retrieve documents and draft summaries or edits in place is very attractive. For example, contract review AI that connects to the firm’s contract repository to analyze documents directly is useful. If a tool requires attorneys to manually copy-paste data in and out, that’s a security risk and a nuisance.

- Microsoft Office and Email: Many firms are excited about AI that integrates with Microsoft Word, Outlook, etc., because that’s where lawyers spend time. Microsoft 365 Copilot is one example (when it becomes widely available) – it will be an AI assistant embedded in Word/Excel/Outlook that follows enterprise security rules 103. Firms will evaluate those integration points closely. If an AI product can’t integrate and would require lawyers to use a separate interface extensively, it might face adoption hurdles.

- Enterprise IT Compatibility: The AI platform should comply with the firm’s IT requirements – e.g., single sign-on, specific cloud providers if any, compatibility with VPN, etc. Firms often involve their IT and InfoSec teams to run penetration tests or security assessments on new AI software. Only if it passes these will it be greenlit.

- Scalability and Performance: Law firms also consider performance metrics – both speed and capacity. If an AI tool is painfully slow or rate-limited such that it can’t handle the firm’s usage patterns, it’s not viable. Conversely, a tool that can significantly speed up a process (e.g. review 100 NDAs and produce a summary report overnight) adds clear value 104. Firms might run small scale trials to ensure the tool can handle large documents or multiple simultaneous queries from many lawyers, etc.

- Ethical and Regulatory Compliance of the Tool: In addition to performance, firms give weight to whether the AI tool or vendor follows ethical AI principles that align with the firm’s own obligations:

- Bias and Fairness: Firms may ask the vendor what they have done to mitigate biases in the model. For instance, have they tested that the model’s outputs don’t systematically favor or disfavor certain groups (which could be a concern in something like employment law AI)? The firm has a duty not to propagate bias, so if a tool had a known issue here, it could be a red flag 105.

- Auditability: Can the firm get logs or records of AI interactions for audit purposes? Some enterprise AI solutions provide an admin dashboard where usage can be monitored – useful for compliance and for investigating any incidents. Because attorneys must supervise AI, having audit logs is a plus.

- Alignment with Professional Rules: Firms check that using the tool won’t inherently cause ethical breaches. For example, if a tool’s terms of service claimed ownership or rights over outputs or allowed the vendor to access client info, that would conflict with confidentiality duties 106 107. So those terms must be negotiable or absent. Another example: if a contract analysis AI made legal conclusions on its own, the firm would still ensure a lawyer reviews them to comply with law practice rules (since non-lawyers/AI can’t practice law). The tool must be flexible enough to allow that “human in the loop” approach.

- Firm-Specific Custom Solutions: Some large firms decide that none of the off-the-shelf solutions fully meet their criteria, and opt to build or heavily customize their own AI platforms in partnership with vendors. For instance, a firm might take an open-source large language model and train it on its internal data, creating a proprietary AI assistant only for its lawyers. This path is resource-intensive but gives maximum control over data and tuning. A hybrid approach is working closely with a vendor like Harvey (which several law firms are doing): the vendor provides the AI tech, but fine-tunes a model exclusively for the firm, using the firm’s data, and deploys it privately for that firm 108 109. This essentially yields a custom AI that speaks the “voice” of the firm’s knowledge. The Harvey example with Allen & Overy shows the model was trained on A&O’s historical work and then locked to A&O 110 111. U.S. firms are exploring similar options with various providers. The advantage is such a model can be very accurate on the firm’s common tasks and by design will not leak data outside (since the model instance is firm-specific) 112 113. The downside is cost and complexity. Each firm must assess if it has the scale to justify that.

- Formal Procurement Process: In practice, the decision of which tools to implement goes through a formal review. A typical process might involve:

- Initial Pilot by Innovation Team: The firm’s innovation or knowledge management team identifies a promising AI tool and does an initial pilot on sample problems (with dummy data) to gauge usefulness.

- Security & Risk Assessment: Simultaneously, the firm’s IT security group and risk management lawyers evaluate the vendor’s security, the terms of service, compliance with privacy laws, and ethical risks. They use checklists or frameworks (e.g., an AI vendor due diligence checklist) to ensure nothing is overlooked.

- Feedback from Lawyers: The firm gets input from a group of lawyers who would be end-users – is the tool actually helpful? does it save time? what errors did they see? This is important because a tool might be safe but useless, or useful but with caveats – the firm needs that perspective.

- Internal Approval Committee: Many firms have a technology or innovation committee (including partners from various practices and IT leaders) that will review the pilot results and risk reports and make the final call. They weigh the cost-benefit: does the efficiency or capability gained outweigh any risks? If yes, they approve the tool for use, often starting in a limited way (e.g., approved for the litigation practice group only, or for non-confidential projects first).

- Training & Rollout: Once a tool is approved, the firm will train attorneys on how to use it properly (tying in the policy guidance). Clear instructions are given, for example: “You may now use \[Tool X] to help draft documents, but remember to follow our AI policy – no sensitive info should be entered, always review the output, etc.” The tool might be integrated into the firm’s software portal for easy access.

In essence, law firms treat AI platforms as high-risk, high-reward investments that require thorough vetting. No firm wants to be the headline for a data breach via an AI tool or a malpractice issue from an AI mistake. Thus, the bar for selection is high. The five key criteria outlined in a recent buyer’s guide by LexisNexis capture it well: privacy & security, model capabilities, answer quality, performance, and ethical guardrails 114 115. By evaluating prospective AI tools against those factors, firms aim to choose solutions that deliver real value (speed, insight) in a reliable and responsible manner 116 117.

The table below compares how law firms’ approaches can vary along a spectrum – from very restrictive usage to moderate controlled use to progressive adoption – highlighting differences in internal policies, client disclosure practices, and tool selection criteria under each approach:

Approach

Internal AI Use Policy

Client Disclosure

AI Tool Selection

Restrictive("Prohibit or Minimal Use")

Early adopters of caution. In 2023, some firms banned or severely limited staff use of generative AI for work. Policies said no client data in any AI and often temporarily barred using tools like ChatGPT entirely until guidelines were established. Attorneys were told to rely on traditional methods; any AI experimentation had to be offline and not involve real cases. The emphasis was on waiting for more secure solutions.Keywords: “Do Not Use ChatGPT”, “Confidential info stays out of AI”, “Wait for approval.”

Generally avoided AI entirely, so disclosure was moot. These firms assured clients that they were not using unvetted AI at all on their matters. If an attorney did wish to use AI in a specific case, it would require explicit client consent. Otherwise, engagement letters did not mention AI (since the firm’s stance was not to use it). Clients with strict policies (e.g. some banks) found this acceptable.Keywords: “No AI without client consent”, “Default: No AI use on matters.”

Very high bar for tools. These firms likely had no AI vendor approved initially. They focused on monitoring the landscape. Any consideration of a platform was slow and ultra-careful. They might test an AI product in a sandbox, but would only implement once it had a track record and met stringent privacy standards. Often waiting for enterprise-grade versions of AI (e.g. waited for OpenAI’s business offering or Microsoft’s integrated Copilot) before adopting.Keywords: “Not until proven secure”, “Small pilot only”, “Prefers on-prem or none.”

Controlled("Guided Use with Guardrails")

Most large firms by 2024 fall here. They allow use of AI but under strict guidelines: no confidential data in public tools, verify all outputs with human review, and use only approved platforms. Policies are well-defined and training is provided. AI can assist with research, drafting, summarizing – but attorneys must follow all the policy steps (check for accuracy, etc.) and never rely on AI without independent analysis.Keywords: “AI is permitted with caution”, “Always verify AI output”, “Only use approved AI apps.”

Emphasis on transparency and client choice. Many have added engagement letter clauses disclosing possible AI use under supervision. They generally inform clients that AI might be used to improve efficiency, while assuring oversight and confidentiality. If a particular deliverable involved AI, the lawyer might mention it. They also explicitly respect any client request opting out of AI use. The default is to be open and avoid surprises.Keywords: “May use AI tools to assist (with supervision)”, “No client data fed into AI”, “We will discuss AI use as needed.”

Thorough vendor vetting but willing to adopt good solutions. These firms have approved certain AI tools that passed security review (e.g. a legal research AI from a reputable vendor, or an NDA review tool that runs on a secure cloud). They look for enterprise versions with privacy guarantees. Selection criteria focus on data protection, accuracy, and legal-specific capability. Many integrate these tools into workflows (e.g., adding an AI drafting assistant into Word for attorneys). They typically start with a pilot, then scale usage once the tool proves its worth and safety.Keywords: “Only vetted tools (privacy, quality)”, “Preferred vendors (legal AI with citations)”, “Gradual rollout after pilot.”

Progressive("Embrace & Innovate")

A few leading firms actively embrace AI at scale. They still enforce core rules (no confidentiality breaches, human oversight), but they encourage attorneys to find new use cases for AI and share success stories. For example, at one Am Law firm, over 800 personnel use generative AI daily for various tasks under a comprehensive policy framework. These firms often have an AI committee updating internal policies in real-time and providing on-call guidance.Keywords: “AI-friendly (with rules)”, “Firmwide AI adoption initiative”, “AI training required for all attorneys.”

Highly transparent and collaborative with clients. These firms position their adeptness with AI as a benefit to clients. They proactively tell clients about AI-driven efficiencies (e.g., faster document turnarounds) and how they manage risks. Some may include detailed explanations in engagement materials about their AI governance. They remain ready to turn off AI for any client who is uncomfortable, but many of their clients are themselves tech-forward. In some cases, firms in this category work with clients to develop shared protocols for AI use.Keywords: “Upfront about AI to clients”, “AI as efficiency selling point (with safeguards)”, “Client can opt in or out to certain AI uses.”

Leaders in experimenting with advanced AI. These firms often partner with AI developers or invest in proprietary AI systems. They might deploy a custom-trained model on their internal data (a private legal GPT). They choose tools that can deeply integrate with their knowledge systems – sometimes even building solutions in-house. They also tend to run multiple AI tools for different purposes (one for research, one for document automation, etc.), each carefully evaluated. The selection still prioritizes security and quality, but these firms are willing to be early adopters of innovative platforms – for example, being beta testers for new legal AI products – to stay ahead.Keywords: “Building custom AI with partners”, “Multiple best-in-class AI tools in use”, “Data stays internal (firm-trained models).”

Table: Comparison of firm approaches – Some firms took a very restrictive stance initially, barring any use of generative AI on client matters, whereas most now allow controlled use under strict guidelines. A few are forging ahead with broad adoption of AI, having put comprehensive safeguards in place. The approaches differ in how internal policy is enforced (from “no AI” to “AI with oversight”), how much they disclose to clients about AI involvement, and how willing they are to integrate cutting-edge AI tools into their systems. Every firm has the same fundamental concerns – confidentiality, accuracy, and ethics – but they balance innovation and risk differently.

Emerging Standards and Best Practices

Across these domains (internal use, client disclosure, tool selection), clear best practices are emerging industry-wide. Drawing on bar association guidelines and the collective experience of firms so far, here are some of the key principles likely to shape AI policies at law firms going forward:

- Never Compromise Confidentiality: This is non-negotiable. No sensitive client information should be fed into AI tools unless (a) the client has consented and (b) the tool is secured such that the data cannot leak or be seen by others 118 119. If there’s any doubt, don’t put the data in. Many firms use the rule: “If you wouldn’t email the info to an outside party, don’t input it into an AI.” As the California bar put it, lawyers must “ensure content will not be used or shared by the AI product in any manner” without authorization 120 121. This will remain a bedrock rule.

- Maintain Competence – Know the Tech: Lawyers must understand the capabilities and limits of AI tools they use 122 123. That means training and self-education. It’s becoming expected that competent representation includes being up to speed on helpful technologies (comment 8 to ABA Model Rule 1.1 says as much). So, firms should continue to invest in educating their attorneys on how AI works, common pitfalls (e.g. hallucinations), and proper usage. An informed lawyer is less likely to misuse the tool or be fooled by it. In short, treat AI like a junior colleague whose work must be evaluated critically – and give that “colleague” a proper orientation.

- The Lawyer is Always Ultimately Responsible: No matter how sophisticated AI becomes, law firms will hold to the principle that lawyers cannot abdicate responsibility to a machine 124 125. AI doesn’t have a law license; the attorney signing the brief or advising the client does. So policies will continue to mandate human review, supervision, and accountability for any AI-assisted work. This aligns with ethics: a lawyer can use AI just as they use a paralegal or a draft from another attorney, but they must supervise and verify to meet standards of diligence and accuracy 126 127.

- Disclose AI Use When it Matters: While there’s no blanket requirement (yet) to announce every time AI is used, the safe approach is to be candid with clients whenever AI use could be deemed important to them 128 129. This could be upfront in an engagement or at key junctures. The ABA opinion 512 doesn’t force disclosure in all cases, but it emphasizes communicating about means to accomplish objectives 130 – which many interpret as encouraging discussion of AI as a means. The likely best practice: include a standardized clause in engagement letters about AI, and if a client objects, document that and comply. If a client is fine or even encouraging about AI, also document that. In court filings, expect that disclosing AI assistance (or at least being ready to on inquiry) will become normalized, especially as more judges require it to guard against fake citations.

- Bill Ethically & Share Benefits: A subtle but important practice – if AI significantly reduces the hours needed for a task, pass some of that efficiency to the client (in fees or alternative billing arrangements). ABA Formal Op. 512 specifically warns that you can’t charge as if you did something manually if an AI did it faster 131. Firms that embrace AI will likely use it as a competitive advantage by handling matters more cost-effectively. Being transparent in billing – e.g., noting when a task was accelerated by technology – can build trust. Clients generally don’t want to pay for a lawyer’s time learning a tool, only for the time using it to their benefit 132. So firms are adjusting billing guidelines internally: time spent reviewing AI output is billable, time spent figuring out how to prompt the AI might be seen as overhead.

- Continuously Monitor Developments: The regulatory and technology environment around AI is in flux. Best practice for firms is to stay updated on new ethics opinions, court rules, and laws about AI. For example, if a jurisdiction enacts a rule explicitly about AI use disclosure or data handling, firms need to immediately incorporate that. Likewise, keeping an eye on technology trends – new AI tools that are more secure, or new features like watermarking AI-generated text, etc., can inform policy tweaks. Some firms schedule periodic policy reviews every 6 months given the pace of change. The goal is to ensure the firm’s policies are always aligned with the current best knowledge and standards. The ABA and state bars are expected to continue issuing guidance; firms will be following those closely 133 134.

- Empower an “AI Governance” Team: Many experts recommend that firms establish an internal committee or officer for AI oversight. This group can evaluate tools, handle questions from attorneys, and ensure compliance. It’s similar to having a privacy officer or a chief information security officer – now a designated person or team for AI ethics and usage. This is a best practice because it centralizes expertise: instead of each lawyer guessing, they have a resource for guidance. Some firms have merged this role into existing innovation teams; others appoint tech-savvy partners or IT leaders. This team also often handles training programs and creates reference materials (like an internal FAQ: “What to do if you want to try an AI on a case?”). ALA (Association of Legal Administrators) and others have suggested cross-functional committees (including lawyers, IT, and risk managers) to oversee AI adoption.

In conclusion, U.S. law firms are rapidly developing a framework to integrate AI in a way that enhances service but maintains ethical and professional integrity. Internal policies set the guardrails for safe AI use by attorneys, client-facing policies ensure transparency and consent, and careful vetting of AI tools protects against undue risk. The overall message is cautious optimism – firms acknowledge that AI can be a powerful ally for efficiency and insight in legal practice (indeed, it might soon be indispensable), but they are proceeding with the same deliberation and duty of care that they apply to all aspects of legal work. By adhering to emerging best practices – protecting confidentiality, insisting on human oversight, communicating openly, and choosing tools wisely – law firms are striving to make AI “court-approved” and “client-approved” as a permanent part of modern legal services 135 136. The policies and approaches outlined here will no doubt continue to evolve, but they lay a strong foundation for the legal profession to innovate responsibly with artificial intelligence.

Tammy Anthony Baker, CISSP

New Orleans and South East Information Technology Group

.png)

.png)